Wine is part of a tradition that¡¯s connected to the soil and that the people who maintain that tradition continue to make the wine that¡¯s most worth drinking.

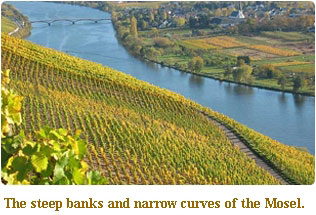

The Mosel (previously named as Mosel-Saar-Ruwer) wine area is located in the southwest part of Germany, 100 km west of Frankfurt near the French/Luxembourg border. It starts from Vogesen Mountain in France and then it flows to Perl, as the ¡¯three-country¡¯ corner of France, Luxembourg and Germany, to enter the border of Germany. The Mosel flows for 544 km in total to join the Rhein at Koblenz.

The valley of the Mosel together with its tributaries, the Saar and the Ruwer, with nearly 9,533 ha (23,555 acres) of vines, is Germany¡¯s fourth largest winegrowing region, but number one in terms of Riesling vines (5,523 hectares/ 13, 650 acres). It is also the largest and most important Riesling production area in the world. Over half of all Mosel wine is Riesling. Slightly more than |

|

three quarters of the wine produced here is QbA and somewhat less than one quarter is higher quality QmP wine. Only one percent is table wine.

There are lots of wine-villages along the Mosel area. From just south of the ancient Roman city of Trier, north to Koblenz, where it empties into the Rhine, the Mosel River snakes its way past dramatically steep, slaty slopes covered with the very best vineyard sites which produce some of the worlds most highly prized Riesling wines.

This region is the northern-most fine wine region in the world, a region where there very often is not even enough sunlight to ripen the grapes to maturity, however its unique climate, slate and viticulture suit for Riesling which is a very-late-ripening grape and can grow well in a cooler region. As Terry Theise, the |

|

world¡¯s most inspired and inspiring advocate for great German Riesling indicated, the world¡¯s most fascinating, meaningful and delicious wines are made from grapes grown where they belong, in the soils and climates that suit them.

Riesling wine from the Mosel has the ability, virtually unique in the world, to bring into play with style and finesse its wonderful rich mineral notes and lively, vibrant acidity even in the classically half-dry, sweet and botrytis dessert categories. The paradigm for German Riesling is pure fruit flavors often reminiscent of peaches, pear or when young, apples, faithfulness to the soil, and balance of all structural components so that neither sweetness nor acidity stands out.

Along the serpentine route of the Mosel, the river banks rise so sharply that the vineyards carpeting these slopes are among the steepest in the world, with some planted at an astounding 70-degree gradient.

|

|

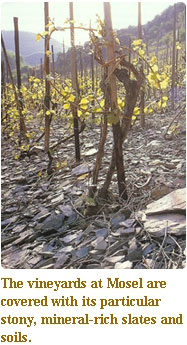

The benefit of steep slate-covered slopes is often explained in relation to the aspect of the sun each vineyard enjoys. Naturally, south-facing slopes have a great advantage here. Another very important aspect of the slate-covered steep slopes is also the fact that these soils will heat up rapidly and to a considerable degree when the sun shines, giving the vines a decisive advantage in their maturation in many phases throughout the year. Besides, rivers are acting as a heat reflector, helping to maintain a constant temperature day and night. In autumn the mist and fog that raises from the river offers the grapes protection from early frost.

By virtue of this double warming effect, the dark slate soil absorbs a tremendous amount of solar energy during the day, which is then gradually released to the vines throughout the night. Cold or excessive waterlogging is unknown here. Falling rain is rapidly absorbed by the soil, but is prevented by the many stones and gravel from forming troughs and eroding the valuable soil.

Although the advantaged natural conditions make quite some top-quality sites available at Mosel, each vineyard site, and sometimes even within a single site, this interplay of factors takes place each year, with subtle differences and variations, depending on the weather. Particularly for wine making at Mosel, one of the coldest and northernmost wine growing regions in the world, depends much more considerably on weather conditions.

In addition to the general climate, it is important to consider the micro-climates of individual vineyard. The direction and inclination of a particular slope, the intensity of sunshine reflected from mirroring rivers, a protective ridge of hills or a forested mountain summit, which deflects the wind - all help the wine achieve its ultimate taste and quality.

Vineyard sites are not brands and wine making is also a delicate of art. They vary, and thus contribute to the challenge and interest of the winemaker¡¯s work. The winemaker¡¯s viticultural practices, cellar technology, the decision when to harvest and his creativity can direct and determine all the important factors, thus reacting to both the happy and difficult aspects of a year¡¯s weather conditions. That is why in bad vintage, a good winemaker still can make reasonably good Riesling wine at Mosel.

Wine production here is a tough, backbreaking job and in that way, little has changed in the last 2000 years. On these precipitous inclines, nearly all labor must be done by hand. The mechanization that has made the lives of vintners in other areas so much easier has proved difficult or impossible to apply to many of the Mosel¡¯s steep slopes. Careful work and almost exclusively manual work is indicated all year round under these conditions, not just at harvest time. From pruning and weeding to the harvest itself, most of the work is still done by hand. That includes tying each vine to its own eight-foot wooden stake, and carrying up the slate soil that has washed down with the winter rains. Therefore only those who do love the wine and plan to excel, have chosen the life to stay here. That is why people say: "if you¡¯re a young guy making wine at all along the Mosel, you¡¯re probably making excellent wine".

|

Winemakers at Mosel employ traditional methods of wine growing and winemaking which have been used in the Mosel for centuries, some of which date back to the Romans. For example, the vines are grown on the traditional single-post ¡¯Heart-binding¡¯ trellis system, whereby the canes are tied in the shape of a heart. Most importantly, yields are kept at low levels in order to achieve intense and well-structured wines. For optimal flavor development, leaves are thinned and grapes are harvested as late as possible to allow for maximum ripening. All grapes are hand picked and carried from the vineyard in traditional shoulder-mounted containers called ¡¯hotten¡¯ to ensure optimal fruit quality.

On the other hand, many of vines at Mosel are old or even very old, some of them ungrafted, and are able even in dry years to draw water and minerals as deep as 30 meters. It is this interplay, the battle of the wine to make the best of the natural conditions of the site (today often referred to as terroir), that in each vintage ensures the fascinating spectrum of aromas and tastes of Riesling wines from the Mosel. This is the source of the mineral and often also spicy tension, providing the appropriate balance for both sweetness and acidity, preventing any thought that the wines might be one-dimensional or boring.

Mosel valleys are the setting for some of the world¡¯s most beautiful and romantic wine countries. The Mosel is riddled with historic towns from Trier to Koblenz and provides for a most scenic journey and unique travel opportunities. Divided into three sections, the upper, middle and lower Mosel, the adorable towns along its banks have been settled for thousands of years.

The opportunity to experience the Mosel first hand is awe-inspiring. The traditional time for a trip to Mosel is the grape harvest in the autumn, until the first frosts provide the conditions for the deliciously sweet and aromatic Eiswein. The sampling tingling new wine (Federweissen) and spicy Zwiebelkuchen (onion pie) are part of the typical pleasures of the Mosel region. Sitting along the mighty banks of the Mosel, indulging on the fruits of the land, drinking the crisp and delicious Riesling so full of minerals and acidity is heaven on earth. Match that with the talents of amazing vintners and famed vineyard sites such as Piesporter Goldtröpfchen, the Brauneberger Juffer , Trittenheimer Apotheke or Merler Königslay Terrassen and you will truly taste a quality that belongs to only one Riesling, the Mosel Riesling. Just one visit to Cochem, referred to by many as "the romantic town," or a visit to Bernkastel-Kues, one of the first Mosel settlements, where artifacts dating back to the Stone Age (4000-3000BC) have been found, and you will be astonished. With over 75 historic towns along the amazing 240km journey inside Germany, there is something for everyone. Known as Europe¡¯s oldest independent cultural landscape, it is an incredible sight to be seen.

Overview of Mosel Wine Region

Geographical Location:

The Mosel Valley, a gorge the river carved between the Hunsr¨¹ck and Eifel hills, and the valleys of its tributaries, the Saar and Ruwer rivers.

Major Towns:

Koblenz (confluence of the Mosel and Rhine rivers), Cochem, Zell, Bernkastel, Piesport, Trier.

Climate:

Optimal warmth and precipitation in the steep sites and valleys.

Soil Types of Vineyard:

Clayish slate and greywacke in the lower Mosel Valley (northern section); Devonian slate in the steep sites and sandy, gravelly soil in the flatlands of the middle Mosel Valley; primarily shell-limestone (chalky soils) in the upper Mosel Valley (southern section, parallel with the border of Luxembourg).

Vineyard Area (2003):

¡ó 9,533 ha / 23,555 acres¡¡¡¡¡ó 6 districts¡¡¡¡¡ó 19 collective vineyard sites¡¡¡¡¡ó 500 individual sites.

Number of Winemakers:

66,400 wine growers.

Quantity of Vines:

88 million vines.

Grape Varieties [white 91.7% , red 8.3%] (2003):

Riesling (56.8%), M¨¹ller-Thurgau (16.1%), Elbling (7.2%) ¡ª an ancient variety cultivated by the Romans and because of its pronounced acidity, often used as a base wine for Sekt, Germany¡¯s sparkling wine ¡ª as well as Kerner, Bacchus and Spätburgunder.

Marketing:

About one fifth of the region¡¯s grape harvest is handled by the regional cooperative cellars in Bernkastel-Kues. Overall, the producers of bottled wine are cooperatives (13%), estates (28%) and commercial wineries (59%). The latter also bottle and market a healthy quantity of wines from other German wine-growing regions (e.g. the Pfalz and Rheinhessen) as well as less expensive, imported wines. Much of this production is exported. Nevertheless, direct sales to final consumers is an important sales outlet for smaller growers, who benefit from the region¡¯s tourism. Zell, Bernkastel and Piesport are among the few German appellations of origin with a recognition value far beyond their borders.

Click here to discover and enjoy the Mosel region.

| |